Who Gets to Make Art?

AI tools widen access but democratising creativity threatens those who say art should only be done a certain way

🌸 ikigai 生き甲斐 is a reason for being, your purpose in life - from the Japanese iki 生き meaning life and gai 甲斐 meaning worth 🌸

I watched a 7-minute anime this week that was made with AI.

Anyone who has messed with AI image or video generation will know how difficult it is to maintain a consistent character, clothes or even image style. Oh and they usually only create about 10 seconds of video at a time.

I think the video is really slick, I mean yeah the story isn’t my cup of tea, but it IS really impressive that they were able to create something so coherent. The creator spent weeks crafting prompts in Gemini, generating images, feeding them into Sora, creating dozens of separate clips then painstakingly stitching them together.

Some people say “this is not real art”, purely because of the tools used rather than anything about the quality of the end result, or the skill needed to achieve it.

This week I also had a really interesting chat with a friend about whether or not it’s feasible to detect AI use in an application process, that just so happened to be for an art competition.

People seem to be asking for tools to catch cheaters, those using AI to game the system, when they ask about tools for AI detection. Rather than curiosity about why the artist chose that method.

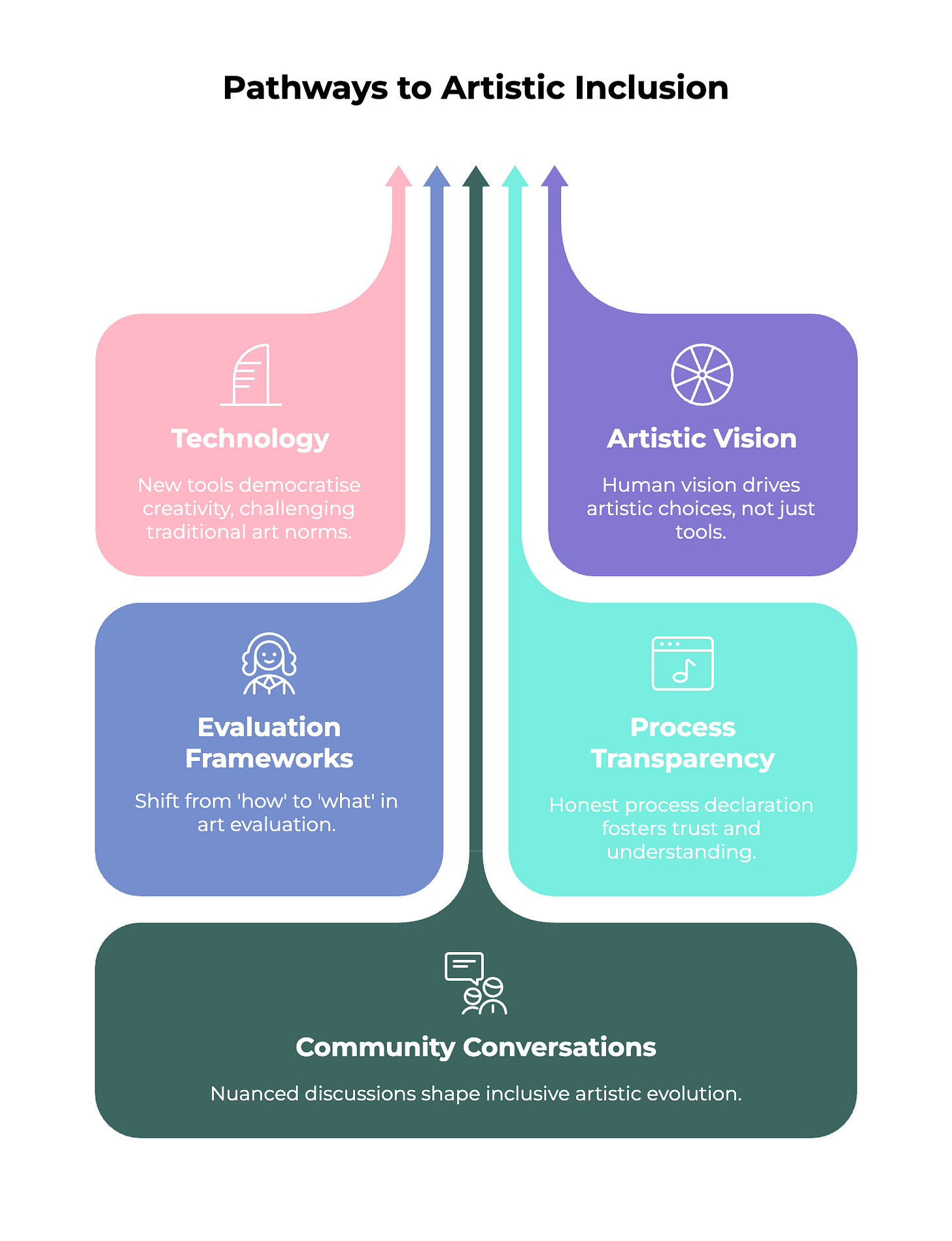

I know ‘let’s ban AI’ is a tempting position to take for some aspects of art, but I’m keen to have nuanced conversations on a community level about whether that is feasible and what risks there are to it even if it were. It’s interesting to dig deeper into the why and explore what we value and what we are really trying to achieve, individually and collectively, and find ways to inclusively evolve as well as honouring people’s choices.

It does though make me wonder why we are so desperate to prove how something is made, rather than celebrating what was made?

This feels familiar. Like I’ve watched this film before, just with different technology in the starring role.

We’ve panicked about this before

Every generation faces a technology that makes creativity more accessible, initially rejected as “not real art”.

Photography wasn’t real art because you just pressed a button, anyone could do it. Where was the skill? Real artists understood light and shadow through laborious practice.

Synthesisers weren’t real music because you didn’t pluck strings or blow into instruments. You just pressed keys, anyone could make sounds. Real musicians had calluses and lung capacity.

Digital art wasn’t real because you just clicked a mouse, anyone could undo mistakes. Where was the commitment? The permanent choices? Real artists lived with their brushstrokes.

CGI animation wasn’t real because you just modelled on computers, anyone could make characters move. Where was the physical labour? Real animators spent years moving plasticine millimetres at a time.

Notice a pattern? “Anyone could do it” is a complaint that reveals what this is actually about.

Not quality. Not artistic merit. Not difficulty. Not emotional impact.

Access.

When technology lowers barriers to entry, those who cleared the old barriers can feel threatened. I understand that instinct, I really do. You spend years developing skills, building expertise, earning your place. Then someone shows up with a tool that lets them skip steps you considered essential.

It maybe feels like they didn’t earn it.

But Wallace & Gromit and Toy Story are both brilliant. Stop-motion plasticine and CGI can coexist. Both require vision, both require choices, both require mastery. Just different media.

Nobody says Pixar “cheated” because they didn’t physically move objects.

So why are we hearing that now about people using AI tools?

When tools become invisible

I wear glasses, have done since I was ten. They’re assistive technology that lets me see things.

Nobody accuses me of “cheating at vision”.

Writers use spell check. Designers use colour theory tools. Architects use CAD software. Musicians use recording and mixing software. Photographers use image editors. Every single creative discipline uses technology to augment human capability.

We only call it “cheating” when the technology is new enough to threaten existing power structures.

Think about a musician with arthritis who can no longer play physical instruments but can compose with software. The person with aphantasia who can’t “see” what they want to draw but can describe it to AI. The working parent who has two hours not 200 hours but still has something vital to say.

Why would we want to prevent these people from making art?

Every iteration of technology in every sphere allows us to do more with less. Agriculture. Medicine. Communication. Transport. Education. Why would art be different? And more importantly, why would we want to gatekeep who can make it?

Perhaps some of the resistance to AI tools is about preserving scarcity, and therefore value and status. If anyone can make good looking art, what happens to those who spent years learning to make good looking art the hard way?

I have empathy for that anxiety. Your skills feel devalued. Your investment feels wasted.

But the skills don’t disappear, they shift and you have a choice. It is entirely valid and will hopefully always be valued to not use AI at all in your art. For others though you may see benefit in embracing the different expertise available now. The ability to direct, to curate, to orchestrate, to navigate entirely new types of creative constraints.

The problems are tangled together

Before anyone jumps down my throat in the comments... yes, I know most of these models learned from artists who weren’t compensated, and I don’t like that. I also dislike the fact that modern systems, and let’s face it much of society as a whole, don’t value artists more highly.

Putting any of our creativity online is a risk, but many feel the internet with it’s global access and digital channels also provide opportunity, ways to build an audience and income streams.

I pay for music because I adore it. I try to patronise artists whenever I can. I gladly support my favourite writers. Same with visual art, with good TV series and films. I genuinely believe in compensating creative work. I’d pay even more to hear artists talk about why they made what they did which is why Patreon is such a fab model.

It’s worth untangling though the economic devaluing issue, labour rights and copyright questions from the “is it art?” question for AI use.

Conflating them avoids harder conversations.

The IP and compensation issues are real, important and need addressing through policy and regulation. Artists deserve payment for their contribution to training data, they deserve paying full stop. That’s about fairness and economics.

But it’s separate from the question of whether someone using AI tools is making “real” art.

We can solve the compensation problem AND acknowledge that AI-assisted creation can be legitimate artistic practice.

They’re not mutually exclusive.

Moving beyond detection

When people ask me about AI detection, I want to have a MUCH longer conversation than they’re expecting *grin*.

Can detection tools ever be 100% accurate? They disproportionately flag certain writing styles, non-native speakers, neurodivergent creators. They create false positives that could destroy someone’s reputation or opportunity.

Worse of all though, I think they’re usually trying to solve the wrong problem.

The problem isn’t “did someone use AI?” The problem is “did someone create something original and meaningful through their own vision and choices?”

Those are completely different questions.

Here’s what I think artistic communities need instead of detection;

Declaration of process. “I used AI to brainstorm initial concepts, took a co-authored story outline in to Google Docs but then wrote the finished piece myself.” “I crafted all prompts myself, used Midjourney for guide image generation, then painted my vision in oils” Whatever the truth is.

Multiple evaluation frameworks. Maybe we need categories, “Traditional Craft” / “Hybrid Digital” / “AI-Orchestrated”, so work is judged by appropriate standards. Or maybe we stop categorising entirely and just ask… is this good? Does it move us? Does it contribute something valuable?

Conversation over application forms. A 15-minute chat about artistic choices reveals everything. “Why did you choose this composition?” “What were you trying to evoke?” “What options did you reject?” “Walk me through your decision-making process.”

Someone who only pressed a button once can’t answer those questions with any depth.

Someone who orchestrated hundreds of generations and stitched them together absolutely can.

The evaluation shifts from “how was it made?” to “what choices did the artist make?”, because that’s what art is. Choices. Vision. Intent. Communication.

The tools are just tools.

Democratisation isn’t a dirty word

I don’t think the joy of creation should just be for those who can afford years of training or have the physical capacity for traditional techniques or the time for laborious processes.

When we gatekeep who can make art based on their access to traditional training or tools, we lose voices. Diverse perspectives. Stories that need telling by people who could never access the old systems.

If AI tools help someone who couldn’t access traditional art making... I think that’s beautiful. That’s expanding the conversation. That’s letting more humans express their humanity.

Preserving difficulty seems odd to me, surely the goal is to preserve the meaning.

And meaning comes from humans, whatever tools they use to express it.

I think about ikigai here... that purpose in life that comes from contributing something valuable to the world. If someone has that vision, that desire to create and share, why would we want barriers in their way?

The world needs more art, not less. More voices and perspectives, not a narrower gate.

Every time technology has made art making more accessible, we’ve drawn lines and talked about preserving the old ways as the only legitimate ways.

And every single time, eventually, we’ve adapted. We’ve made space for the new alongside the old. We’ve recognised that different tools require different skills but can produce equally valid art.

This moment is no different.

The panic will pass. The tools will improve. The conversations will evolve.

What matters is that we don’t lose sight of what art is... humans expressing something meaningful through choices that matter to them.

Whether they do that with brushes or code or prompts or clay.

The answer to the question “who gets to make art?” should always be a joyful refrain of “everyone who has something to say”.

So what are you going to say?

Sarah, seeking ikigai xxx

PS - Bullet journal prompts for this week

Tool Audit - List every technology or tool you use in your creative practice (yes, even pencils and erasers). Which ones do you consider “legitimate” and which feel like “cheating”? Why? What does this reveal about your assumptions?

Access Reflection - Think about a time when a tool or technology let you do something you couldn’t do before. How did that feel? Who might be having that same feeling with AI tools right now?

Vision Mapping - Describe a creative project you’ve been thinking about but haven’t started. Now ask yourself honestly… what’s actually stopping you? Is it lack of skills, lack of time, lack of tools or lack of permission you’re giving yourself?

PPS - AI prompt exercise

“I’m struggling with feelings about AI tools in creative work. Help me untangle my thoughts by asking me questions about: What creative skills I’ve developed over time and why they matter to me. What I fear losing if AI becomes more prevalent. What I might gain if more people had access to creative expression. What my real concerns are versus what I’ve absorbed from others’ panic. Then help me craft a personal framework for thinking about AI in art that honours both my expertise and the democratisation of creativity.”

PPPS - Soundtrack for today

“Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles. I know it’s a super cheesy choice, but clearly this 1979 synth-pop hit was about tech changing creative industries, nostalgia for old ways, and anxiety about the new. “Pictures came and broke your heart” indeed.

The historical parallels you draw are really good. They make the debate about access and not art cuts through the noise perfectly.

I also have a personal question I wanted to ask, I left it in your inbox, when you have time, please check it out.

Yes everything I have felt but couldn’t express this precisely. It’s so funny how we humans keep forgetting and how we keep resisting chance. Even if we can’t see the details yet, automatic resistance is such a sad choice as a pose to curiosity. Thank you for this piece of written art 🙏